‘The situation is desperate both for those trapped in conflict-affected areas, with barely any means of surviving, and for those displaced across the province and beyond. Those who remain have been left deprived of basic necessities and are at risk of being killed, sexually abused, kidnapped, or forcibly recruited by armed groups. Those that flee may die trying.’

These words from the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet describe the state of the Cabo Delgado region in northern Mozambique. Plagued by an increasingly violent insurgency, Cabo Delgado is looming humanitarian tragedy – if indeed, it is not so already. But it is more than this. In excess of 2 000 lives have been lost and over 400 000 have been rendered homeless. The insurgency is a matter of profound security concern not only to Mozambique, but also to the region as a whole. It places in jeopardy the developmental prospects of the country, and those of its neighbours. It is a threat that cannot be ignored.

It would be surprising if many South Africans understood what had sparked and sustained the Cabo Delgado insurgency. It is strange phenomenon that a good part of what influences our realities can be traced to obscure corners of the globe in which many of us have limited knowledge and even less awareness. Think Bosnia and Afghanistan, for example. Northern Mozambique is hardly a place familiar to South Africans – it is far from the business opportunities in Maputo and the beaches and cuisine of Xai Xai.

Yet the events in Cabo Delgado are a high stakes game for South Africa. There have been suggestions that special forces are operating in the country; private military contractors certainly are. This could come at a cost. The Islamic State’s online news platform, Al-Naba, said that South African intervention ‘will place it in a great financial, security and military predicament, and may result in prompting the soldiers of the Islamic State to open a fighting front inside its borders!’

State security minister Ayanda Dlodlo says that the situation is giving the government ‘sleepless nights’.

Origins

If Cabo Delgado is far from South Africa’s consciousness, it is also at a remove from the rest of Mozambique, culturally and historically. Predominantly Muslim, it was in pre-colonial and colonial times oriented towards the east African coast and the Gulf. Despite being well endowed with natural resources, Cabo Delgado is Mozambique’s poorest province, and it has also long been sidelined or ignored by the country’s government, receiving little attention for its considerable developmental needs. Chronic corruption and governance failings compound the malaise.

These factors were a combustible mix on their own. But they were seized upon by Islamist ideologues, who sought to fit these grievances into their own narrative. The problem, from their perspective, was not governance pathologies, but the entire nature of society, which needed to reconfigured around a purist form of religion, and an Islamist ideology that was bolted onto it.

It is important to understand what ‘Islamism’ means. It is not simply the observance of the Muslim religion. It is rather essentially an ideology that references the perceived politico-religious demands of the faith – politicised religion, in rough terms. This sort of orientation is not unique to Islam, but has arguably assumed in the religion a prominence that is unmatched elsewhere. There are several reasons for this: the failure of alternative ideologies (secular nationalism and socialism), the triumph of the Shia revolution in Iran in 1979, the seizure of the Grand Mosque in Mecca – also in 1979 – and Saudi Arabia’s turn to extreme religious conservatism, as well as the invocation of religion in such conflicts as the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the Balkan Wars, Chechnya and the various conflicts in the Middle East. Islamism was able to position itself as a fresh, redemptive answer to temporal problems based on Divine law, and enjoying both deep cultural roots and therefore a large degree on legitimacy. Some adherents would choose to pursue this peacefully, others through violence, holy war or ‘jihad’.

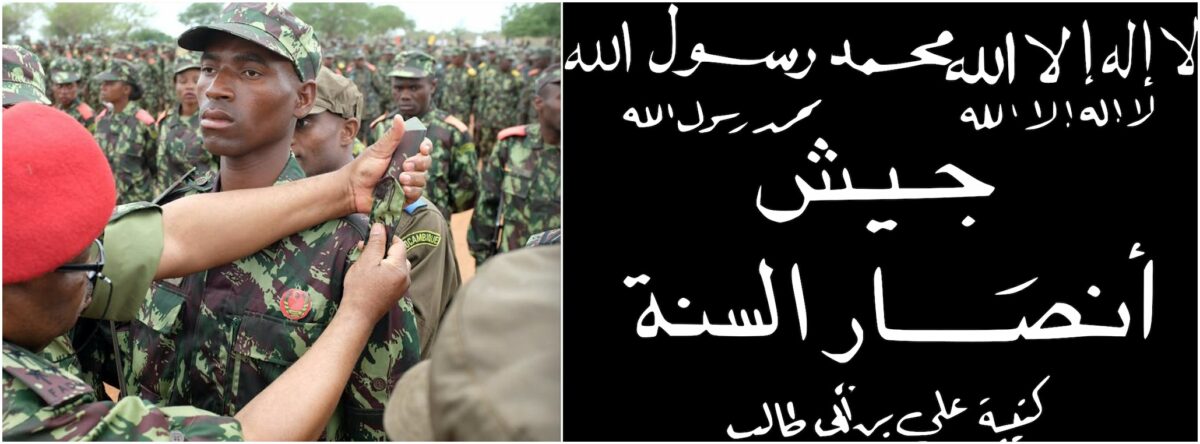

In the circumstances of Northern Mozambique, it was easy for the violent option to take root. Prof Hussein Solomon, one of South Africa’s foremost security analysts, notes that as early as 2004, military training camps had been established in Cabo Delgado. Alongside Mozambicans, recruits from Somalia, Pakistan, Bangladesh and South Africa were receiving training. But it was in 2015, with the emergence of a quasi-formalised group Ansar al-Sunna the insurgency went into high gear.

Expanding objectives

Trained by former police officers and border guards (there are also suspicions of Renamo involvement) – skills that have an outsized market and utility in an unstable environment – Ansar al-Sunna went onto the offensive, targeting the state, the security forces and attempting to force a ban on alcohol.

Amid widespread concern about the deteriorating situation (including from Mozambique’s Islamic authorities), the government intervened. But its measures were tactless and sometimes brutal. Inevitably, this served to drive recruitment from young men feeling alienated and victimised. This is also observable elsewhere: a recent study by Italian researcher Luca Raineri on the rise of the Islamic State of the Greater Sahara argued that state and state-supported counter-insurgency action often provided the impetus for recruitment of supporters.

Around 2018, the Islamic State began talking about its Central African Province. The insurgency, in common with others across the world and in Africa, had in a sense gone global. Indeed, Ansar al-Sunna was not simply carrying out raids and disrupting life. It sought to capture territory. In August this year it did so, temporarily seizing the strategic port city of Mocimboa da Praia, a key logistics node for investments in natural gas.

And in South Africa…

As noted above, the threat to Mozambique has been acknowledged as holding grave dangers for South Africa. Invariably, any attempt to face this challenge in the manner that South Africa would likely prefer – that is, regionally and multilaterally – would impose a leadership role on the country. The possibility of retaliation would be very real.

South Africa is certainly ‘linked’ to extremism and to terrorist groups. South Africa has been used as a safe haven for such groups and individuals associated with them; funding and planning activities have been conducted in the country; South African passports have appeared in the hands of operatives; and there is evidence of training facilities having been established. Osama bin Laden reportedly viewed South Africa as an ‘open’ space where terrorist actions could be carried out. Coupled with porous borders and an often dysfunctional state, South Africa would indeed be vulnerable.

Less clear is the extent of domestic radicalisation. This is an important question – could South Africa fall victim to home-grown terrorism, feeding off local grievances and ideological aspirations and driven by local systems of recruitment and indoctrination?

In reality, South Africa has already had experience of this. In the 1990s, this came to prominence in the emergence of People Against Gangsterism and Drugs (Pagad). Driven largely by frustration with the destructive sway that gangs and gang bosses exerted over predominantly coloured communities in the Western Cape, initial protest action gave way to violence. This in turn appeared to arise from the growing influence of Islamist elements in the group. These were linked to Qibla, which had been established as an anti-apartheid organisation inspired by the 1979 Iranian revolution.

Pagad would later diversify its activities. No longer confined to vigilante activity, it engaged in attacks on putative American and Jewish targets, as well as on symbols of perceived moral decadence and on Muslim critics. The South African state was condemned as immoral and ungodly. It was, in other words, increasingly acting out of ideology.

Although Pagad itself went into decline after around 2002 (several members were convicted of violent offences), Islamist militancy was given a boost by the September 11 attacks in 2001, and US policy in retaliation. On the one hand, the attacks on the US could be seen as a major blow to its prestige and evidence that it was not invulnerable. On the other, the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq by predominantly Western powers reinforced a narrative of Muslim subjugation and oppression. The unresolved situation in Israel and Palestine did likewise.

Interestingly, US and Israeli policy became a cause celebre for a much wider audience than committed Islamists, or even for concerned Muslims. Globally, left wing activists (and some on the right too) rallied to condemn it. In their view, this was an expression of imperialism, and constituted a unique danger to the world. The leftist British journalist Nick Cohen wrote in a book entitled What’s Left that this produced large blindspots towards abuses and ideological pathologies existing within political movements and states hostile to the US and Israel. Arguably, this gave Islamism within the broader anti-imperialism milieu a sort of legitimacy-by-default.

Revealingly perhaps, the Al-Naba editorial referred to above stressed need to protect foreign investments as a key motivator for both the government of Mozambique and the foreign powers that might support it – this is a narrative eminently familiar in secular ‘anti-imperialist’ discourse. It reads:

If the Crusaders reckon that they, in their support for the disbelieving government in Mozambique, will protect their investments and guarantee the continuation of their plunder of the resources of the region, they are delusional, as it won’t be too long before things become consolidated in favour of the soldiers of the Caliphate.

This is perhaps illustrated by the case of Mustafa Jonker. An aspirant jihadi, he was suspected of planning a terror campaign in South Africa and arrested on a battery of charges (later dropped after the state failed to provide the reasoning behind the raid that produced the charges). He set out his position in an interview as follows:

I, like thousands of Muslims like me am concerned at the plight of the oppressed in general and the Muslim Ummah in particular, which over the last century has witnessed an unprecedented onslaught from global disbelief. I realized from an early age that America is the main source of this global tyranny by her directly invading Muslim lands and killing their people and also by supporting apostate governments that subdue their people on her behalf. We returned to South Africa in 1999 [from Saudi Arabia] and I soon realized that while the racist apartheid regime had been removed, this new ‘democracy’ had come about by the African National Congress selling South Africa to multi-national corporations. The ANC has a history of concern for only the middle and upper class blacks. The result of this treachery is a symbolic multicultural government which is dictated to by and passes laws on behalf of mainly European and American companies, the same Crusader nations pillaging Afghanistan and Iraq today. Today South Africa has the biggest gap between rich and poor in the world; a direct result of the government’s neoliberal capitalist policies. A wealthy elite own South Africa’s wealth, while 30 million people suffer from poverty. Resulting from this poverty is crime of which South Africa has the highest statistics in the world as well. I began advocating as Allah commanded direct action against the Crusader-Zionist alliance and her pawns in power and this is the background behind my being labelled a terrorist. As far as this word goes, it is a label placed on anyone challenging the greedy bloodthirsty agenda of the West and I therefore take a pride in it. Ours is a blessed terror that desires to see an end to America’s oppression.

His position blended Islamic religion, identity, geopolitics and domestic grievances. He went on to express some harsh anti-Semitism.

Prof Solomon notes too that Islamist ideology has been driven on by experiences of the past two decades. South Africa has seen a number of Muslims travel to jihadi hotspots such as Afghanistan, Iraq or the IS controlled areas of Syria. Many have returned with their beliefs fortified, and their abilities to wage such a jihad sharpened..

He also points out that Islamist ideas have been infiltrating Muslim theology in the country, this being largely the result of an influx of scholars trained in foreign madrassahs. To this, one might add the influence of the internet and social media. This has made Islamist ideology accessible to an ever-expanding audience, competing with the conservative and accommodating strand of Islam that has historically prevailed in South Africa. This combination – the internet and Islamist classes – appears to have been behind the radicalisation of the Tony-Lee and Brandon-Lee Thulsie and their associate Renaldo Smith.

Moving forward

It is clear enough that the threats to South Africa differ markedly from those in Mozambique. South Africa does not face a warband-style insurgency of the type that is taking place in Cabo Delgado. It is nonetheless serious. Terrorism carried out by committed lone-wolves or by autonomous cells of committed operatives can wreak devastating damage. This has been repeatedly demonstrated, and by no means only by Islamists – think the Japanese Red Army Faction’s attack on Lod Airport in 1972, the Strijdom Square massacre in 1988, or the Christchurch Mosque shootings in 2019.

Violent Islamism or jihadism is almost certainly endorsed by very small numbers of people in South Africa and in the region – small relative to the society, and small relative to the Muslim population. Small numbers but great commitment are nevertheless a grim combination. Defeating it will need to proceed along two lines.

The first is on the field of security. This implies both counter-insurgency (in circumstances like Mozambique) and effective law enforcement (in those obtaining in countries like South Africa). This naturally raises questions about the efficacy of the security forces in the region to handle this task. In particular, the critical need for reliable intelligence is complicated where the relevant agencies have been politicised or focussed on fighting internal battles, or might have been undermined by corruption – or even penetrated by those they are meant to be countering. There is already evidence that problems in South Africa’s security forces have undermined action against jihadis. And even relatively wealthy societies with highly professional intelligence apparatuses have found merely monitoring potential threats to be a Herculean task.

The second is even more difficult. This is the ideological side of the matter. How to combat an idea which – in the social context and intellectual framework of its holder – seems perfectly logical and morally correct? It has often been said that this is a battle that only Muslims themselves can win. This is probably correct, although no less daunting a task for that. Indeed, established Islamic authorities may well be seen as part of the power structure that Islamists oppose. There is simply no easy solution here, and no perfect one, since it is well nigh inconceivable that even a highly successful campaign against radicalisation would be effective in each and every case.

But the need to take firm and effective action is not something that can be ignored. The damage and destabilisation that even a limited campaign of jihadi violence could do is something that the region and South Africa can ill afford. Indeed, in the early days of South Africa’s democracy numerous political and academic voices argued that a failure to deal with the debilitating problem of violent crime could undermine the entire democratic project. This particular problem remains very much an issue – and compounding it with a jihadi threat might well threaten the viability of South Africa as a constitutional democracy.

South Africa is already an unstable mess! Let Islamic terror take over and it will become an irredeemable train wreck!